- Home Page

- Fact Tours

Our sample tour itineraries of China and China travel packages are sorted by theme and available at competitive prices, you can browse what tours are right for you for your trip to China.

Popular China Tour Packages

Custom Tour Packages to China and Ask Our Experts for Free Enquiry !

- Coach Tours

- Destinations

Beijing, the capital of China. Its art treasures and universities have long made it a center of culture and art in China.

Beijing Top Attractions

Beijing City Tours

Best China Tours with Beijing

Shanghai, the cultural and economic center of East Asia. It renowned for its historical landmarks, the extensive and growing skyline.

Shanghai Top Attractions

Shanghai City Tours

Best China Tours with Shanghai

Xi'an, having held the position under several of the most important dynasties. It is the top destination to explore the facts of Chinese history.

Xi'an Top Attractions

Xi'an City Tours

Best China Tours with Xi'an

Huangshan boasts its culture, beautiful rivers, villages and mountains. It's home to 2 UNESCO World Heritage Sites and the Mecca of photographers.

Huangshan Top Attractions

Huangshan City Tours

Best China Tours with Huangshan

Sichuan is the cradle of the Shu culture, panda, mahjong, teahouse and spicy food. The province ranks first in China by number of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. It is called "the Heaven of Abundance".

Sichuan Top Attractions

Sichuan Tour Packages

Best China Tours with Sichuan

Yunnan, literally means the south of colorful clouds, due to its beautiful landscapes, mild climate and diverse ethnic cultures and traditions, is one of China's major tourist destinations.

Yunnan Top Attractions

Tibet, the nearest land to the sky, is known for its breathtaking landscape, splendid culture, art, buildings, and mysterious religions.

Tibet Top Attractions

Tibet Tour Packages

Best China Tours with Tibet

Explore the lost civilizations by riding a camel! Travel across the Gobi and the desert, and over the high mountains. Our Silk Road tours including different sections of the Silk Road in China.

Silk Road Top Attractions

Silk Road Tour Packages

Best China Tours with Silk Road

Guilin, an internationally-known historical and cultural city, has long been renowned for its unique karst scenery. Its vicinities are the paradise of hiking, caving, rafting, biking and countryside exploring.

Guilin Top Attractions

- China Facts

- China Hotels

- Travel Photos

Arts and Crafts

- Chinese Silk

- Chinese Sculpture & Carving

- Chinese Quyi

- Chinese Shadow Puppet Show

- Chinese Pearls

- Chinese Paper Cut

- Chinese Painting

- Chinese Music

- Chinese Lacquer Ware

- Chinese Wushu or Kung Fu

- Chinese Jade

- Chinese Games

- Chinese Dances

- Chinese Culture

- Chinese Ceramics

- Chinese Calligraphy

- Ancinent Chinese Bronze Vessels

- Chinese Acrobatics

Chinese Games

Traditional Chinese Games

Classic Chinese games are a very important part of Chinese culture. When traveling in China, you stroll through the streets and you'll see and hear people playing Chinese traditional games for relaxation, fun and more. You'll also see plenty of interested onlookers watching and commenting on the strategies and moves of the players. A brief introduction tells what games Chinese play for relaxation and mental stimulation.

Ancient Chinese games like chess (xiang qi), encirclement chess (wei qi), which is similar to chess, and checkers (tiao qi) are popular board games. Tile games such as mahjong (majiang) and dominoes (gu pai) are also keenly played - just walk by virtually any apartment block, day or night, and you're sure to hear the loud click-clack of mahjong tiles being moved about.

Why are Chinese traditional games like these so popular? Chinese tile games and board games are not only enjoyable, they're also challenging. They therefore require brain usage, which is why middle-aged and elderly Chinese in particular like to play them regularly. According to traditional Chinese longevity principles, playing games that are fun, relaxing and mentally challenging is an ideal way to improve and maintain your mental health and help slow the decline of old age.

While you may not enjoy games like chess or checkers, it is important that you have your own ways of relaxing and stimulating your brain. The saying, "use it or lose it", definitely applies to your brain! If you're looking for ways to relax, improve your thinking and memory and cope with anxiety, stress, worry and other negative emotions, start doing breathing exercises - they're a simple, extremely effective method for calming your mind, balancing your emotions and greatly improving your overall health and wellbeing. Chinese Chess

Chinese Chess

Xiangqi, or Chinese Chess, is an extremely popular game in the world, especially in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is currently played by millions (or tens of millions) in China, Taiwan, Thailand, Singapore, Vietnam, Hong Kong and other Asian countries. Xiangqi has remained in its present form for centuries.

In China, you often can see people play the game on street using a large chess set. Some players may hit the board hard at some moves to show his power. Since the pieces are large (about 2 inches in diameter), the effect is dramatic. They may also say or sing something to do the trick. Usually there are a few people watching the game. If they know both players (sometimes even they don't know the players), they may point out some moves for one or both players. To prevent the helpers to say anything during a game, the players often remind them by saying 'watching but not telling, a true gentleman'.

Chinese Chess is very easy to play, but the rules are very different from 'Western Chess'. Once you know the rules, you just need practice to get better like anything else. The Internet is a good place to start since you can always find somebody to play. See more

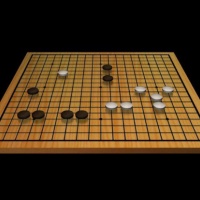

Chinese Go (Weiqi)

Go or Weiqi is most popular in China, Japan, and Korea. Go is a much deeper game than Chinese chess. Chinese chess is more a folk game and go is more popular in those with higher education. I am not a good player, but I find that observing games played by some of the best players in the world has as much fun as playing a game myself. While observing, you can guess the next move the player might move, so you can learn from it. Even I am a really poor player, I might find out some bad moves made by those world class players. The thing is the game really get your attention and you have to think about it. The game is just like life. We start from nothing, then we add a little bit more at each move. We make some good moves and some bad moves. At one point, it becomes so complicated, we can't even figure out what to do or what's the best move, but we have to. We often call go 'the black and white world'.

Go Introduction

Legend says Yao invented go in order to instruct his son Dan Zhu. Yao was a semi-mythical emperor of the 23rd century BC, so go might be invented around 4,000 years ago! Go belongs to one of the Four Arts, qin (music), qi (go), shu (poetry and calligraphy), and hua (painting), in ancient China.

Go is easy to learn, but much harder to become a master of the game. Go is the game of boundary and the winner occupies more space on the board. The rules of go are relatively simple. Here is the official rules of the American Go Association (AGA). For more information, see the Compendium of Rules for Wei-Qi (Go, Baduk) by Wilfred J. Hansen. Observing is an important step to learn go, though playing the game is a more important step. Books are also very useful. The Internet makes all of these much easier now. To play the game on the Net is just a few clicks away. See more

Majong (Mahjong)

Majong (Mahjong)

Majong or Mahjong is a gamblers' game in China. If you don't put money in the game, there will be not much fun. Most people in China play the game using some faked money or a few dollars in the game just for the sake of gambling. Majong was forbidden during the the Cultural Revolution (1966 - 1976) and it is now popular again. You might even hear the playing sound when you go near the windows or the door of your neighbor at night. Since majong is associated with gambling, unlike Chinese chess or go (weiqi) (both are very popular official games), no official majong competition is held anywhere in China.

Mahjong Introduction

Majong was invented long long time ago in China. There are many theories about the origin of majong. A majong set has 144 beautiful tiles, which may be classified into four suits, the bamboo, circle, character, and wind. In each suit, there are 36 tiles. The wind suit includes the flowers, dragons and winds. American majong sets usually have 166 tiles.

To learn majong, you need to know some basic rules of the game. There is a good note of the game by Nanette Pasquarello. Need more information on majong, please go to the majong page. Also majong books are very useful.

Chinese Cards Playing

Chinese playing cards date from at least 1294, when Yen Sengzhu and Zheng Pig-Dog were apparently caught gambling in Enzhou (in modern Shandong Province). The law case notes that nine paper cards and thirty six taels of zhong tong period (1260-1264) paper currency were seized, along with wood blocks for printing cards. Unfortunately, we do not know anything more about the total number of cards in the pack or the markings, etc. Our next source is from the writings of the Ming dynasty scholar Lu Rong (1436-1494), who notes that he was sneered at for not knowing how to play cards when he was a government student at Kunshan in modern Jiangsu Province. (Source: Andrew Lo "The Late Ming Game of Ma Diao" in The Playing-Card journal, Volume XXIX, Number 3, I.P.C.S.).

Questions & Comments

Home | About Us | Partnerships | Terms & Conditions | Privacy & Security | Payment Guide | Resource Links| Sitemap

Email: contact@chinafacttours.com, Tel: +86-773-3810160, Fax: (+86) 773-3810333

Copyright © 2008-2020 China Fact Tours. All rights reserved

![]()